Introduction to ASP .NET Core MVC API

Up to this point, we have been learning about .NET Core and VS Code, about ASP .NET Core, the Startup class, Routing and how to use JSON Configuration.

In this article we will be looking at ASP .NET Core MVC, more specifically at how to build an API that can be consumed from any type of application, be it web, mobile or desktop.

We will build a very simple application that will enable the creation of posts (much like messages) and that will take us through adding the MVC services, creating models, controllers and consuming some data.

We will start this article by building on the code form the Startup class tutorial.

Adding the MVC services to our application

The first thing we have to do is add the "Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc": "1.0.0" dependency in project.json, then add the ConfigureServices method in the Startup class.

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddMvc();

}

Now we have to register some routes for the incoming requests, in this case, any incoming requests that match /api/{controller}/{action}/{id?}.

{controller}- the name of the controller (for example,TestController-/api/test)

{action}- the name of the method from the controller

{id?}- optional parameter passed to the method

So a request for

/api/test/hello/3will be mapped toTestControllerin theHellomethod which will have 3 as parameter forid.

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app)

{

app.UseMvc(routes =>

{

routes.MapRoute(

name: "default",

template: "api/{controller}/{action}/{id?}"

);

});

}

Note that you can customize your route template in any way, I chose the

/apioption because in previous versions of ASP .NET (Web Api) this was the default route for creating an API.

At this point, we can add a controller and make some requests to test our framework. So let’s add a controller, I will call it PostsController and it will have a very simple method that will return a string.

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

public class PostsController : Controller

{

public string Hello()

{

return "Hello from MVC!";

}

}

To run the application, execute dotnet restore and dotnet run in the root of the project and browse to http://localhost:5000/api/Posts/Hello. If everything works, you should see the message received from the controller.

Adding the Post class

As we said earlier, each user that enters can publish a post containing his user name and a text, so our Post class only contains two properties for the UserName and Text of the post and an Id.

public class Post

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string UserName { get; set; }

public string Text { get; set; }

public Post(int id, string userName, string text)

{

Id = id;

UserName = userName;

Text = text;

}

public Post() {}

}

There is also a constructor without arguments, and one that takes arguments the three properties.

If you add a constructor in a C# class, the compiler will no longer create the default constructor, and JSON serialization needs a parameterless constructor when serializing and deserializing objects.

Creating an IPostRepository interface

In order for our API to work, we are going to need a way for it to store data. Regardless of where that data is going to be stored, there should be a consistent way of reading and writing, and we will achieve this through an interface, IPostRepository, that will expose the minimum necessary methods: a method to read all posts, a method to add a post and a method to retrieve a post with a specified id.

So the interface should look like this:

using System.Collections.Generic;

public interface IPostRepository

{

List<Post> GetAll();

Post GetPost(int id);

void AddPost(Post post);

}

Since this is a very simple example, we are going to store the data in a list in memory, but regardless of the location, the publicly available methods will be exactly the same, making any modifications to the data store easy to implement (more on this later).

Creating an in-memory implementation of IPostRepository

We will implement the IPostRepository interface through an in-memory class we will call PostRepository that will hold the data in a list.

private List<Post> _posts = new List<Post>()

{

new Post(1, "Obi-Wan Kenobi","These are not the droids you're looking for"),

new Post(2, "Darth Vader","I find your lack of faith disturbing")

};

Since we have the three methods to access the data, there is no need to expose the post list outside the class, so it will be private. Besides the list, we only need to implement the three methods from the interface, so here is the full PostRepository class:

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

public class PostRepository : IPostRepository

{

private List<Post> _posts = new List<Post>()

{

new Post(1, "Obi-Wan Kenobi","These are not the droids you're looking for"),

new Post(2, "Darth Vader","I find your lack of faith disturbing")

};

public void AddPost(Post post)

{

_posts.Add(post);

}

public List<Post> GetAll()

{

return _posts;

}

public Post GetPost(int id)

{

return _posts.FirstOrDefault(p => p.Id == id);

}

}

The PostController class

ASP .NET (MVC Core and other versions) maps requests to classes called controllers that are responsible for processing incoming requests, handling user input and generating the response (by themselves or by calling other services).

We will create a very simple PostController that will have methods to get all posts, add a post and retrieve a single post based on the id.

The controller will have some instance of IPostRepository(we will see shortly how it will have it) and will call methods from the repository.

using System.Collections.Generic;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

public class PostsController : Controller

{

private IPostRepository _postRepository { get; set; }

public PostsController(IPostRepository postRepository)

{

_postRepository = postRepository;

}

public List<Post> GetPosts()

{

return _postRepository.GetAll();

}

public Post GetPost(int id)

{

return _postRepository.GetPost(id);

}

public void AddPost([FromBody]Post post)

{

_postRepository.AddPost(post);

}

}

Notice how the

AddPostmethod accepts aPostparameter. Because it has theFromBodyattribute, the framework will automatically try to map the body of the request to an object of typePostthat is deserialized from JSON.

Besides from the publicly exposed methods of the API (any public method placed in a controller is publicly accessible from the web), we also have a constructor through which we can provide the appropriate implementation of IPostRepository and we will specify this in the Startup of our application.

Registering the repository service in Startup

So far, we have created an IPostRepository interface, implemented it in PostRepository and used it in PostController(without creating any instance). So if we ran the application right now and navigated to http://localhost:5000/api/Posts/GetPosts we would get a null reference exception simply because we haven’t specified what instance of IPostRepository our application is supposed to use.

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddMvc();

services.AddSingleton<IPostRepository, PostRepository>();

}

We only need to specify that whenever someone needs an IPostRepository, the framework should provide them (the same) instance of PostRepository. So when the PostController constructor has a parameter of type IPostRepository, the framework will provide an instance of PostRepository.

We added the repository as singleton because of the in-memory implementation: if we made a new instance of

PostRepositoryfor every request, then the post list would be instantiated every time, not saving the modifications.

Startup.cs

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Builder;

using Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;

public class Startup

{

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddMvc();

services.AddSingleton<IPostRepository, PostRepository>();

}

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app)

{

app.UseMvc(routes =>

{

routes.MapRoute(

name: "default",

template: "api/{controller}/{action}/{id?}"

);

});

}

}

Testing the application

At this point, we can either execute dotnet run in the root of our project or press F5 in Visual Studio Code.

We will use PostMan for Google Chrome in order to test the functionality of our API.

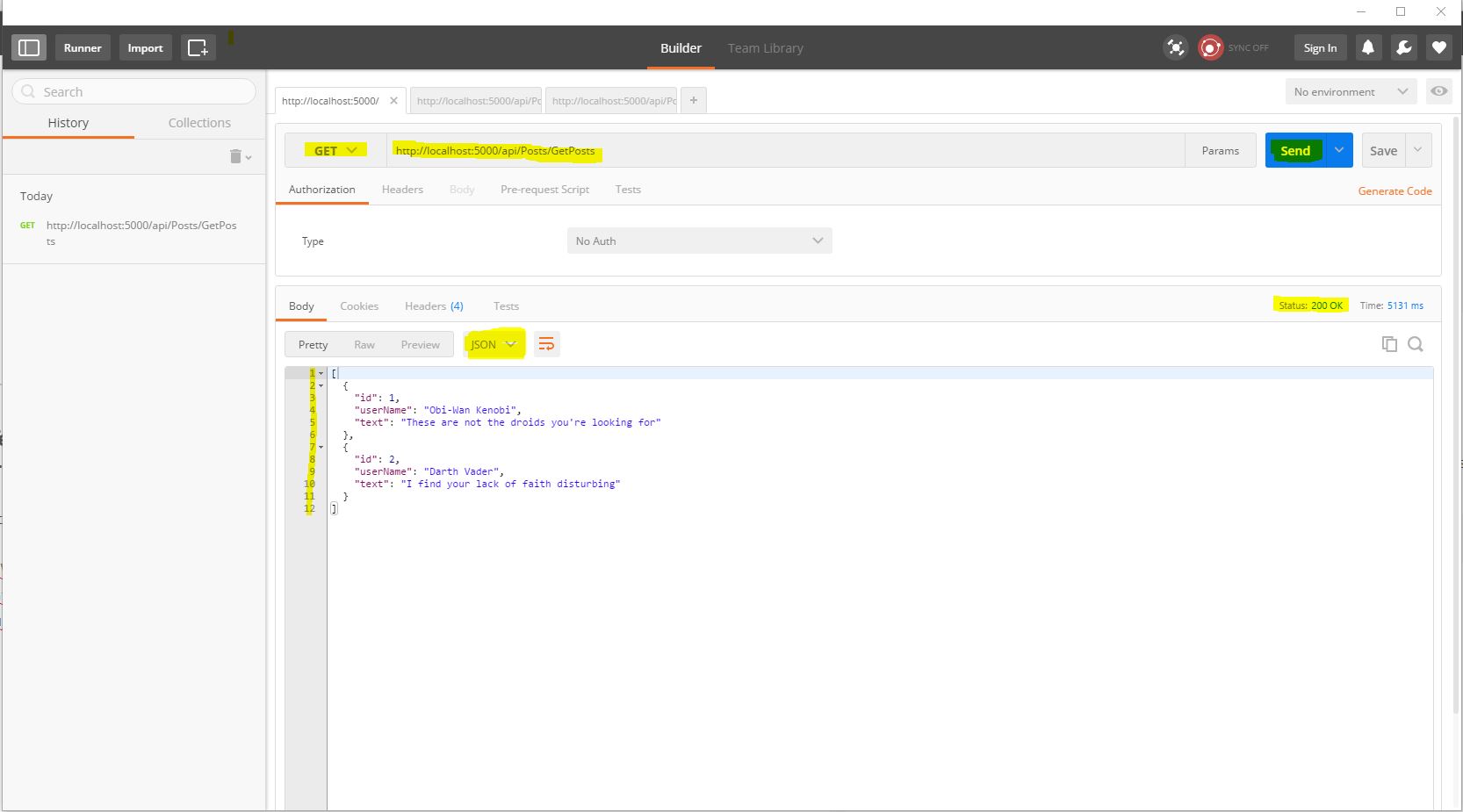

If we open PostMan and create a GET request to http://localhost:5000/api/Posts/GetPosts, we will see the two posts that we used to populate the list in PostRepository.

We can see that the response was JSON and it returned a 200 OK HTML code.

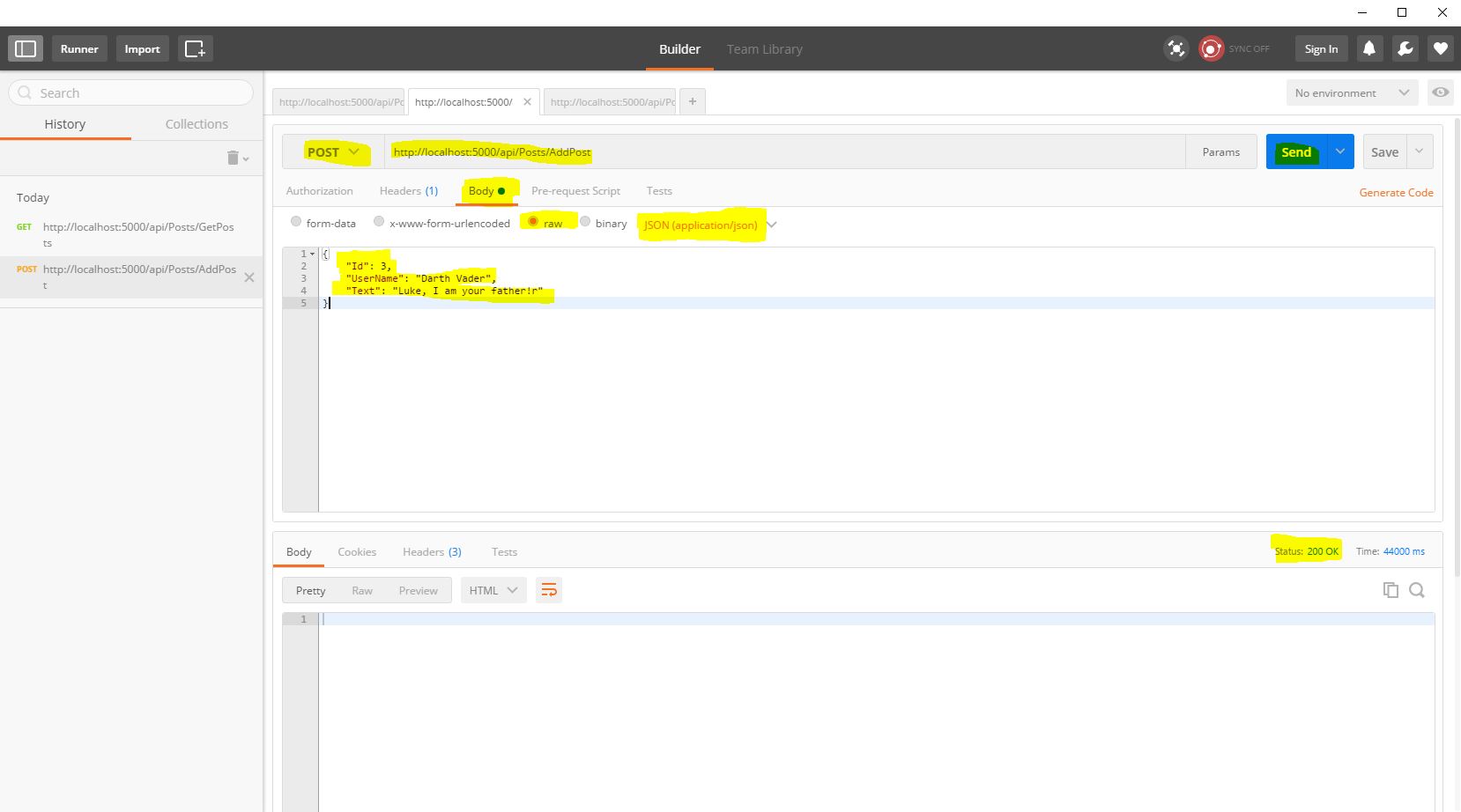

In order to test the post functionality, we create a POST request to http://localhost:5000/api/Posts/AddPost with a JSON object containing the properties of a Post.

{

"Id": 3,

"UserName": "Darth Vader",

"Text": "Luke, I am your father!"

}

You can either use the upper camel case or the lower camel case notation (as you saw in the response from the server, the objects were in lower camel case), but the name and type of the properties must match the ones on the server:

{

"id": 3,

"userName": "Darth Vader",

"text": "Luke, I am your father!"

}

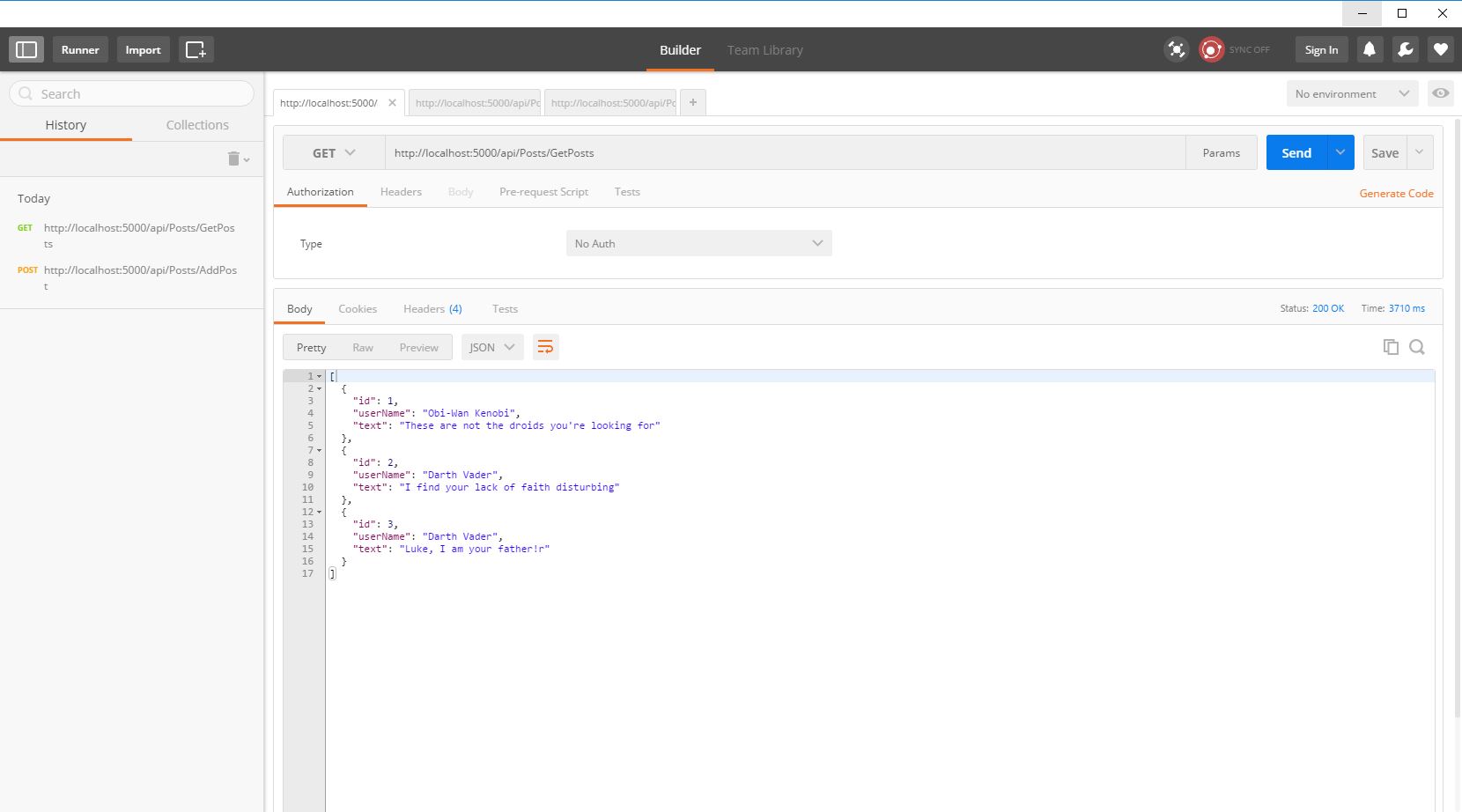

Now, if we create another request to http://localhost:5000/api/Posts/GetPosts we can see that the post we added was saved.

Conclusion

So far we created an API that adds and reads posts from an in-memory data store. A real-life application would have a different type of data store (SQL/NoSQL database) and most certainly an application that consumes this data rather than using it from PostMan.

This API can be consumed from a web application (HTML + JavaScript), a mobile application (virtually any type of mobile application, regardless of the OS), a desktop application (again, any type of desktop application for any OS), even console applications.